York has been there through the thick and thin of British history. The seat of Roman emperors, the landing ground of the Great Viking Army, the capital of the Medieval North. It’s been at the sharp end of civil wars, regicidal conspiracies and industrial revolution.

This rich and varied history is reflected in the city’s architecture. Each building a piece of the mosaic that depicts this place of wonder.

And nestled in the centre of York is Lendal Tower. Like the city itself, the Tower has morphed over the centuries, with bits added, removed and altered according to its changing purpose and the tastes of its owners.

This constant transformation is what gives Lendal Tower its singular character. There’s truly nowhere like it for your weekend getaway in York, and this is its story.

Location

Lendal Tower lies at the western edge of the city centre, perched on the eastern bank of the Ouse as it dips through the city on its southeasterly course. The Tower sits at the southern tip of the York Museum gardens, which were formerly the grounds of the now-ruined St Mary’s Abbey.

From the Tower, you have the entire ancient city within a ten-minute walk. With landmarks such as York Minster, Clifford’s Tower and the York Museum on your doorstep, it’s the perfect spot for a historic city break.

The York City Wall Walk passes right by Lendal Tower, as it runs from the Multangular Tower and crosses Lendal Bridge. The Multangular Tower is just a stone’s throw away. It’s the best-preserved example of Roman architecture in the city and definitely worth a look.

14th Century - Construction

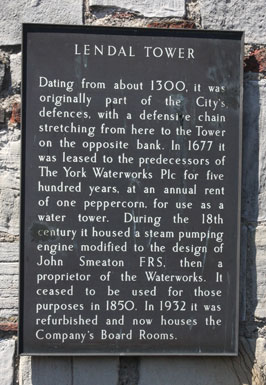

Lendal Tower was first built in 1300 as an addition to the city’s defences. It was first mentioned in the Custody of 1315 as ‘Turrim Sancti Leonardi’ (Tower of St Leonard).

You don’t need to imagine what it would have looked like 700 years ago. You simply need to look across at Barker Tower (also known as North Street Postern Tower), on the opposite bank. Originally, Barker and Lendal Towers were identical, and Barker Tower looks much the same as it did when it was first built all those years ago.

These two little towers not only looked identical – they worked in tandem to perform an important job that helped to ensure the city’s prosperity in Medieval times.

Between these two towers ran a great iron chain, known as a boom. The chain could be raised across the river to prevent ships from passing through without paying their toll. Also, a ferry service ran between the two towers for several centuries, until the construction of Lendal Bridge in 1863.

16th Century - Fortifications

For the first couple of centuries, the Tower got along just fine ensuring the tolls were paid. But in the 16th Century, it found itself in the midst of treason and rebellion…

In 1569, insurrection brewed as the Catholic nobles of the North plotted to depose Elizabeth I, and insert Mary, Queen of Scots in her place – The Rising of The North. Led by the Earls of Northumberland and Westmorland, the rebels occupied Durham, 75 miles to the North, and then marched on York.

The city’s Lord Lieutenant ordered the construction of bulwarks at both Lendal and Barker Tower, should the rebel Earls attack by the river. You can see some evidence of the Tower’s military design in the embrasures (arrow slits) seen on the ground floor of the living area and as you go up the spiral staircase in the northwestern turret.

However, as it turned out, Lendal Tower wasn’t called into action. The rebels never got as far as York’s city walls. The Earl of Sussex led a superior force of the Queen’s soldiers out from York, to meet Northumberland and Westmorland in the field. Outnumbered, the rebels dispersed and fled north into Scotland, and that was that.

The Earl of Northumberland was eventually captured, dragged back to York, and executed on Pavement, a street about half a mile from Lendal Tower. But it would be another 70 years or so before the Tower saw any major military action.

17th Century - Waterhouse

Several attempts were made during the 16th century to convert the Tower into a water pumping station. Finally, an investor named Mr Maltby attempted to initiate a piped water supply out of the Tower. However, this doesn’t appear to have been a success, as by 1646 the Tower was being used as a warehouse and described as ‘much ruinated’. This ruination could have happened during the Siege of York.

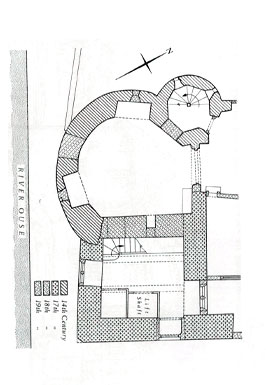

This was a two-month conflict during the English Civil War, where parliamentary forces attempted to take the city from the Royalists. It’s possible that Lendal Tower sustained damage during a bombardment. This may have resulted in the destruction of the original northern and eastern walls, which would have been rounded like the western and southern sides.

The siege ended in July 1644, when the outnumbered Royalist army surrendered. The Tower then enjoyed thirty years of relative peace before it was leased by Henry Whistler of London, who proposed a new scheme for supplying water. On 1st April 1677, the Tower was leased to him for 500 years at a peppercorn rent, once again to be used as a waterhouse.

He was given permission to make improvements and the Tower was enlarged and strengthened to accommodate a lead cistern. This is when the rectangular part of the Tower, on the eastern side, was built. Much of the Tower’s current facing contains reused stone, possibly from the nearby St Mary’s Abbey, situated just a few hundred metres to the northwest, in what is now the Museum Gardens.

Whistler’s initial attempts to use a windmill and waterwheel to raise water were ineffective, so in 1684 a horse-powered water wheel was installed. This would have been in what is now the living area. By 1685, the water supply from Lendal Tower was in full flow.

18th century - Into the Industrial Age

Following Whistler’s death in 1719, the Tower was sold to Colonel William Thornton, who may have used it as a private residence. He then mortgaged the Tower in 1756, possibly to raise funds for the installation of a Newcomen steam engine, which was installed around this time.

In 1779, John Smeaton, the ‘Father of Civil Engineering’, acquired shares in the Tower and its waterworks. From 1781-84, Smeaton set about rebuilding the engine, upgrading it from 4.7 horsepower to 18 horsepower. Upon the work’s completion, the engine could raise 10,500 gallons per hour, for up to eight hours a day.

A pressure gauge from one of the water pumps stands proudly in the Tower’s entrance hall, evoking the Tower’s past life as soon as you enter. And if you take a look around the walls of the Tower, you’ll see some of Smeaton’s original preserved drawings of the engine. You’ll also see the corbels, the protruding brickwork that would have been used to support the engine and upper floors.

19th-20th century - The grandest of offices

Lendal Tower underwent its next great transformation midway through the 19th century. Smeaton’s engine continued running in the Tower until 1836, when it was moved to a new engine house. Ten years later, Lendal Tower’s tenure as a waterworks ended completely as a new facility was founded at Acomb.

With the lead water cistern removed, the Tower was lowered by ten feet and it became the headquarters of the newly incorporated York New Waterworks Company. You may also be surprised to learn that one of the Tower’s most distinctive Medieval features – the crenellated parapet now seen atop the Tower – was only added in Victorian times. It was built in 1846, to designs by prominent York architect, George Thomas Andrews.

The officers of the company eventually felt they needed a grander setting in which to carry out their work, and in 1932, the two upper floors were panelled and decorated in Jacobean style. This panelling is still on display in the first and second-floor bedrooms. The uppermost of these is the master bedroom, and this served as the water company’s boardroom. Evidently, they also grew tired of climbing the stairs, as they added the lift at this time (unfortunately, the lift is not available for guest use – visitors to the Tower today must climb the stairs).

Lendal Bridge - 19th century

No account of Lendal Tower’s history is complete without a mention of Lendal Bridge. This iconic river crossing was designed by Thomas Page, who also designed Skeldergate Bridge and London’s Westminster Bridge. Its elegant Gothic Revival ironwork includes a pair of lampposts, coats of arms and even the initials of Victoria and Albert.

Page’s Bridge, completed in 1863, was the second attempt to span the river at this site. The first, in 1860, failed when it collapsed during construction, killing five men. A year after the bridge was completed, the cast iron walkway seen along the southern face of the Tower was built. This walkway is now known as Dame Judi Dench Way, in honour of the esteemed actress who was born and raised in York.

Spare a thought for the ferryman. The bridge spelled the end for the ferry service that had run between Lendal and Barker Towers for centuries. Apparently, he received compensation of 15 pounds and a horse and cart (about £2,500 and a good-sized hatchback today).

Modern Day

Eventually, the water company moved into more modern offices and the Tower fell into a state of disrepair. It was designated a Grade I listed building in 1954 and, as part of the city’s historic defences, is also protected as a scheduled monument.

After first going on sale in 2004, the Tower changed hands a few times. This was perhaps due to developers being daunted by the maze of planning and preservation requirements involved in renovating the property.

Finally, it came into the possession of Ian Berg, the previous owner, who worked hand-in-hand with York Council and English Heritage experts to ensure the renovation honoured the Tower’s venerable status and history.

Specialist craftsmen from around Yorkshire were brought in, including some who had worked on York Minster, and painstaking work began to not only restore the Tower to its past glory, but to give it a secure future as a supremely comfortable residence fit for modern demands.

It’s our pleasure and privilege to maintain this living, breathing monument to York’s past, and to share it with those who wish to immerse themselves in the city’s rich history.

So if you are looking for an historic city break or a weekend getaway in the centre of York, you can check the Tower’s availability using the booking calendar below. Alternatively, feel free to get in touch if you have any queries.